What is the anatomy of a STARK proof?

Original hackMD, Twitter thread.

This was a question I had while analysing how to implement recursive proofing, otherwise known as a STARK verifier inside a provable environment.

Thank you to: Louis Guthmann for helping connect me and answering my early questions around STARK’s and SNARK’s, as well Kobi Gurkan (who explained R1CS to me), Th0rgal_ for volunteering to tutor me on the polynomial maths, Alan Szepieniec for his fantastic public guide on STARK’s.

Background.

Turns out, STARK’s are really simple! Here are some topics and concepts that will come up during your explorations.

- constraint systems, satisfiability

- Fun question - how do you convert a program into a set of equations?

- arithmetic and polynomial equations

- the idea of a “finite field”, field elements

- Fun question - how come Cairo requires a separate operator for greater-than/less-than comparisons?

- basic interpolation, bonus pts. if you understand FFT

- verifier-prover computation model, interactive vs. non-interactive protocols, Fiat-Shamir transform

- commitment schemes - operations of (commit, open/reveal, verify/prove), merkle trees

- degree of a polynomial, unicity theorem

- FRI protocol, which is basically a binary search.

Simple analogies for common concepts.

- Commitment scheme - basically a generalisation of merkle trees. The merkle root is in essence, a commitment.

- FRI is a binary search for the polynomial to find an area where it fails the low-degreeness test.

- Fiat-Shamir - hashes make people (the prover) commit to things (same idea as atomic swaps), which prevents them from aborting a protocol (like a swap).

- Reed-Solomon - this tech is usually used for error correction - ie. redundantly encode data, so if a bit flips / the cable does something wack, you can still recover the full data. If you look at how Reed-Solomun works, it’s just based on interpolating that data into a polynomial curve, and sampling points from it (redundancy). FRI just uses Reed-Solomun to sample random points for the binary search

ZK-STARK’s - how are they generated?

The best explanation I’ve ever read of ZK-STARK’s is from a cryptographer named Alan Szepieniec, who has written an entire public series here. The diagrams and content below in this section are mostly lifted from his writing.

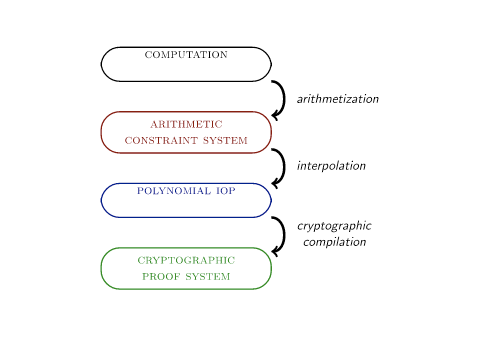

These are the basic steps to generating a STARK proof from running a provable program:

-

Arithmetization. The first transformation in the pipeline is known as arithmetization. In this procedure, the sequence of elementary logical and arithmetical operations on strings of bits is transformed into a sequence of native finite field operations on finite field elements, such that the two represent the same computation. The output is an arithmetic constraint system, essentially a bunch of equations with coefficients and variables taking values from the finite field.

-

Interpolation. Interpolation in the usual sense means finding a polynomial that passes through a set of data points. In the context of the STARK compilation pipeline, interpolation means finding a representation of the arithmetic constraint system in terms of polynomials. The interpolation step reduces the satisfiability of an arithmetic constraint system to a claim about the low degree of certain polynomials - ie. from $x=0$ to $deg (f)$. The resulting object is an abstract protocol called a Polynomial Interactive oracle proof (IOP).

-

Proving low-degreeness. The protocol designer who wants to use a Polynomial IOP as an intermediate stage must find a way to commit to a polynomial and then open that polynomial in a point of the verifier’s choosing. FRI is a key component of a STARK proof that achieves this task by using Merkle trees of Reed-Solomon Codewords to prove the boundedness of a polynomial’s degree. After applying the Fiat-Shamir transform to make it non-interactive, you get a probabilistic proof that at least some high percentage (eg. 80%) of a given set of values represent the evaluations of some specific polynomial whose degree is much lower than the number of values given. This is the STARK.

How can proving low-degreeness be related to proving the satisfiability of the polynomial?

This is a question I had, and didn’t know the answer to! So we investigated.

Problem. How is the problem of arithmetic satisfiability converted into proving low-degreeness of a polynomial?

Answer. Using the unicity theorem of polynomials + blowing up the domain to make it intractable to find a “colliding” polynomial. See [1], [2]

Polynomial unicity theorem. There exists a unique polynomial of degree at most $n$ that interpolates the $n+1$ data points $(x_0,y_0),\dotsc,(x_n,y_n) \in \mathbb {R} ^2$, where no two $x_j$ are the same.

Basically:

- polynomial has roots, where $f(x)=0$

- there is a theorem which relates the roots of a polynomial with the degree

- this is the unicity theorem

- if you can construct the unique polynomial of degree at most $n$, for these roots, then proving the existence of this polynomial (impossible) is equivalent to proving the low-degreeness of the polynomial (possible using FRI)

- problem though - what stops me constructing a polynomial of a similar degree less than $n$, but with completely different values to those in the trace?

- approach is to “blow up” the polynomial’s domain, such that finding a 2nd “exploit” polynomial as described would be intractable according to some security assumptions.

- this is called the low-degree extension. Quoting Starkware:

N. In order to achieve a secure protocol, each such polynomial is evaluated over a larger domain, which we call the evaluation domain. For example, in our StarkDEX Alpha the size of the evaluation domain is usually 16*N. We refer to this evaluation as the trace Low Degree Extension (LDE) and the ratio between the size of the evaluation domain and the trace domain as the blowup factor (those familiar with coding theory notation will notice that the blowup factor is 1/rate and the LDE is in fact simply a Reed-Solomon code of the trace).

Concepts.

- Execution Trace. A series of registers over time.

- Constraints / Trace Polynomials / AIR constraints.

- expressed as polynomials composed over the trace cells that are satisfied if and only if the computation is correct.

- aka Algebraic Intermediate Representation (AIR) Polynomial Constraints.

- Examples:

- transition constraints - program counter

- boundary constraints

- Composition polynomial.

- A combination of the constraints into a single (larger) polynomial, so that a single low degree test can be used to attest to their low degree

- Only used in Starkware’s STARK’s (see ethstark)

ZK-STARK’s - how are they verified?

To verify the validity of the execution trace:

- Read the trace and constraint commitments. (reveal their leaf in the merkle tree)

- Draw pseudo-random query positions for the LDE domain from the public coin

- Read evaluations of trace and constraint composition polynomials at the queried positions;

- For each queried trace/constraint state, combine column values into a single value by computing their random linear combinations.

- Combine trace and constraint compositions together.

- Compute evaluations of the DEEP composition polynomial at the queried positions.

- Verify low-degree proof. Make sure that evaluations of the DEEP composition polynomial we computed in the previous step are in fact evaluations of a polynomial of degree equal to trace polynomial degree. This uses the positions from step (2).

Basically:

- The computation is expressed as both the trace and the constraints. Of course we cannot know the validity of the constraints without the trace values. We use a public coin to seed our selection of positions, and then read the commitments, evaluate the polynomials at those committed positions, combine their values into the composition polynomial, and then do our degree-ness test using FRI.

There is good docs in the Winterfell verifier code. And here’s a summary of the Winterfell verification.

Data structure for a STARK proof.

This section is WIP. Basically I want to document what a STARK proof looks like at the data level.

Circom.

If you look at an implementation of a STARK verifier (e.g. in Circom), you can see the data structure:

- Trace

- Commitment - root of the trace merkle tree

- Evaluations - trace polynomial evaluations at the query positions

- Query proofs - authentication paths of the aforementionned merkle tree at the query positions

- Constraint (transition/boundary) merkle tree.

- Root - termed the “constraint commitment”.

- Evaluations - polynomial evaluations.

- Query proofs - merkle authentication paths to check consistency between the commitment and the queries at pseudo-random position

- FRI.

- Commitments - the root of the evaluations merkle tree for each FRI layer

- Proofs - authentication paths of the aforementionned merkle tree at the query_positions for each FRI layer

- Queries - DEEP

- Misc:

- OOD - out-of-domain - basically boundary constraints.

- pub_coin_seed - serialized public inputs and context to initialize the public coin

- pow_nonce - nonce for the proof of work determined by the grinding factor in the proof options

Starkware.

WIP.

struct StarkWitness {

traces_decommitment: TracesDecommitment*,

traces_witness: TracesWitness*,

composition_decommitment: TableDecommitment*,

composition_witness: TableCommitmentWitness*,

fri_witness: FriWitness*,

}

Misc.

https://hackmd.io/@vbuterin/snarks#Can-we-have-one-more-recap-please